An Exploration of Modern Ginza

An Exploration of Modern Ginza — VI. Mari Mori, “Penniless Luxury,” and Ginza

2021.04.20

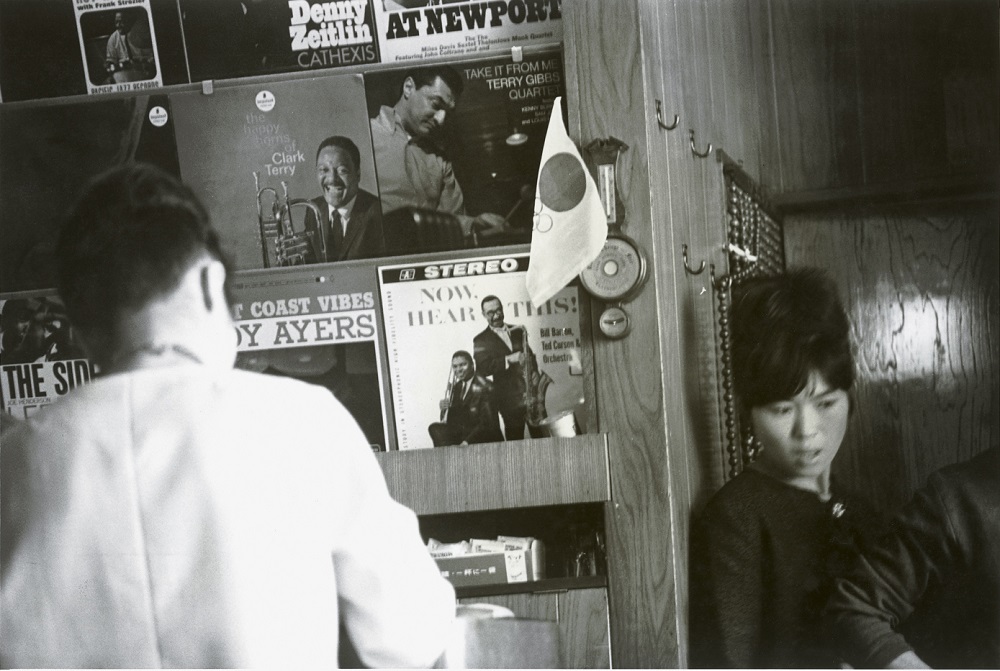

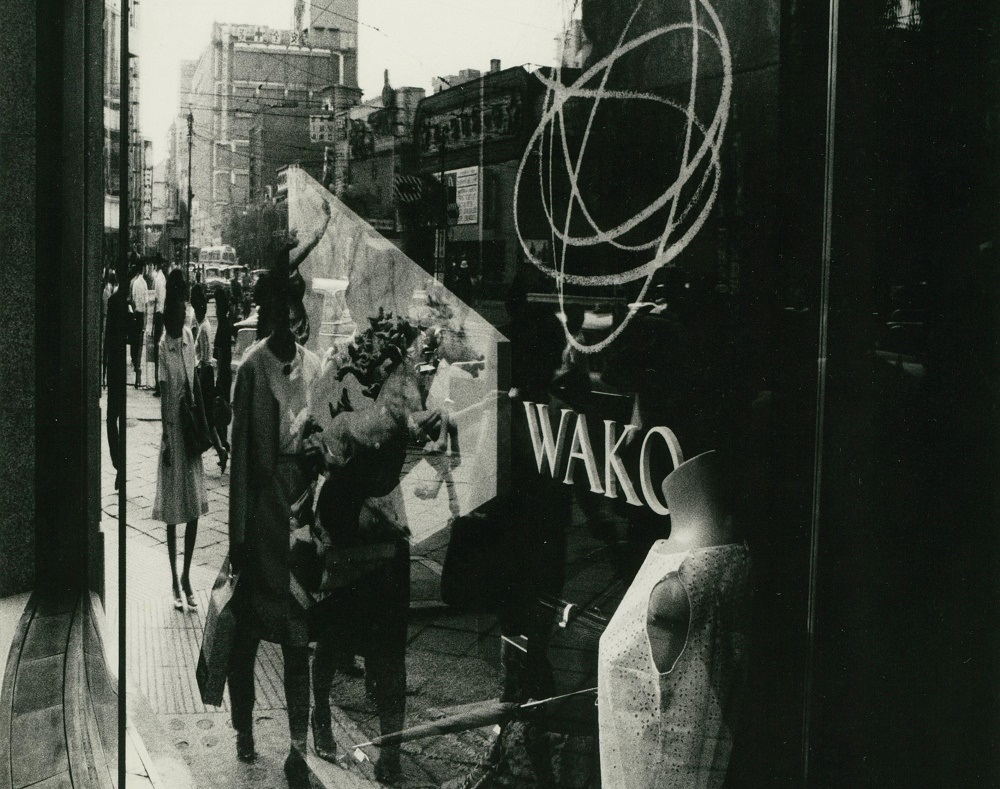

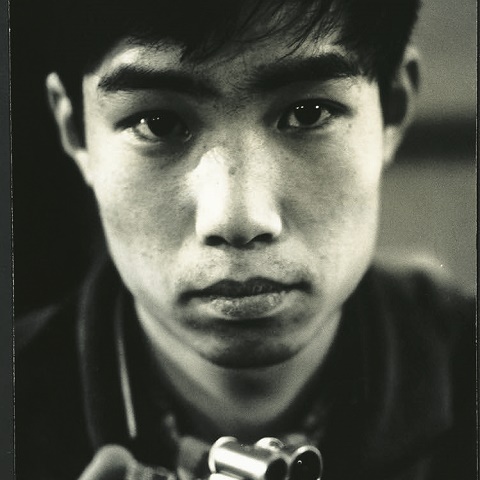

Photography by Ko Ito

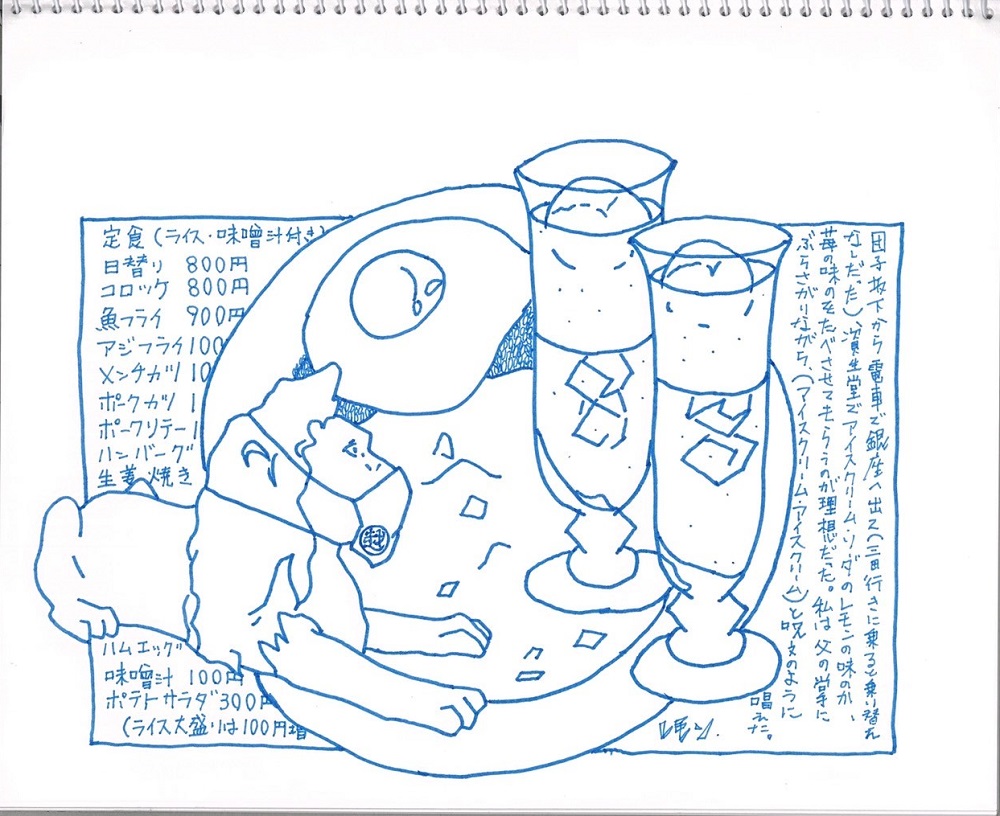

Words & Illustrations by Yoshiyuki Morioka

The Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Hanatsubaki included an essay by Yoshiyuki Morioka, the owner of Ginza’s Morioka Shoten bookstore, on the relationship between Ginza and Shiseido. In this online column, Morioka ties together the past, present, and future of the district through reference to various books and events.

Ginza has always been a stomping ground for iconic figures of the day, and all the excitement and drama that it has seen can be felt in the air even today. So join us on an imaginary walk around Ginza, guided along by the photographs of Ko Ito, a photographer who was taking snapshots of the district around 1964.

VI. Mari Mori, “Penniless Luxury,” and Ginza

The other day I read Zeitaku Binbo (“Lavish Poverty” or “Penniless Luxury”), an essay written by Mari Mori in 1963.*1 After finishing it, it occurred to me that if I were around 20 years old now, I would probably be trying to work out what “penniless luxury” I myself could eke out in today’s Ginza. So, I mapped out a plan on the hypothesis that I had managed to scrape together a budget of 2000 yen (around 18 US dollars) per person by selling some of my stamp collection—just as Mori sold away her jackets to help fund her extravagant ways. (Still, 2000 yen really doesn’t amount to much…)

“You know Mari Mori? She’s the daughter of Ogai Mori [a pre-eminent figure in modern Japanese literature], and she apparently loved the lemon ice cream soda at Shiseido Parlour. They still serve it there—do you feel like going with me sometime?”

That was how I invite A—, a fellow literature student a little older than me, arranging to meet her in front of the lion statue at the Ginza Mitsukoshi department store.

*

Twelve o’clock. The Wako bells ring, and I see A— coming my way. Mitsukoshi’s lion is wearing a mask against the coronavirus, as are we of course.

First, we walk toward the Kabukiza Theatre and turn left onto Showa Avenue to get to Restaurant Hayakawa.*2 After disinfecting our hands, we take a seat by the window and order two curries with fried egg (750 yen each). Through the window, I can see the hydrangeas in bloom along the sidewalk.

“Restaurant Hayakawa was established back in 1936,” I venture. “Mari Mori was born in 1903, so she would have been 33 then. She’d been married and living in Sendai at one point, but she apparently used to complain all the time, saying, ‘Sendai has no Ginza, no Mitsukoshi’ or ‘There’s no Mitsukoshi or Kabukiza here.’”

“But Sendai is such a beautiful city,” replies A—, “and the food there is so good.”

After lunch, we cross to the other side of Showa Avenue and look around the Kabukiza Theatre. I say to A—: "The Kabukiza was designed by Shinichiro Okada, the architect behind buildings like the Hatoyama Hall in Otowa and the Meiji Seimei Kan by Babasaki-mon.” I pause for a while, then continue: “Ogai Mori and Okada’s father, Kenkichi Okada, were both in the Imperial Japanese Army’s medical division under the same superior officer, so maybe they knew each other.” Sadly, this doesn’t seem to interest her too much.

Back on Chuo Street, we make our way to Shiseido Parlour.3 While waiting at the traffic lights on Miyuki Street, I tell her, “You know, Ogai Mori wouldn’t let his children eat ice cream sold on the street—only ice cream in Ginza at Shiseido. He was apparently concerned about hygiene.”

We disinfect our hands again at Shiseido Parlour and sit down at a table by the wall. I find the ice cream sodas in the menu. There are a couple of seasonal flavors too—blueberry and plum—but we decide to go for the lemon one (1150 yen), as that was Mari Mori’s favorite. A— asks the waiter about the painting on the ceiling, and he informs us courteously that it was done by Manika Nagare. After a little wait, our ice cream sodas arrive. Only in Ginza can you enjoy flavors that haven’t changed since Ogai’s days. Then the two of us get to chatting again.

“There’s a Mari Mori essay titled At Dinner One Day, where she talks about the baseballer Shigeo Nagashima’s ‘animal instinct,’ as she calls it. According to her, only a few human beings retain that sharp and adaptable instinct that animals tend to have. The way I see it, that sort of raw, wild instinct is going to be valued even more in the future.”

“Finally, an opinion of your own! I’m into contemporary art, and I get the impression that artists have that animal instinct too.”

“Oh, Mari Mori says something similar. She says that people who achieve seemingly superhuman feats—she specifically mentions Hokusai, Sharaku, Tsuruya Namboku, Saisei Muro, Kyoka Izumi, Shichiro Fukazawa, and Seiji Ozawa—all share that animal instinct.”

“Speaking of art, I hear there’s actually a lot of art to see in Ginza—is that true?”

“I believe so. We should go on an art trail next time!”

So it is that I succeed in securing a next date before our lemon ice cream sodas are finished. All in all, our penniless—well, 2000-yen—luxury outing in Ginza has been a great success.

*2. Restaurant Hayakawa (est. 1936) is one of Ginza’s long-standing Western-style restaurants. Among its most popular dishes are the curry with fried egg, omelet rice, croquettes, and fried fish. 4-10-7 Ginza, Chuo-ku

Contributors

KO ITO

Photographer

Born 1943 in wartime Osaka, Ito was shortly evacuated with his parents to his father’s family home in Wakuya, Miyagi Prefecture. In his sixth year of elementary school, he transferred to a school in Uzumasa, Kyoto, moving there on his own. In 1955 he enrolled at Meiji Gakuin Junior High School in Tokyo, then went on to study at the Tokyo College of Photography from 1961, later joining its teaching department after his graduation in 1963. He held two photography exhibitions during this time. After leaving his post at the school in 1968, he became a freelance photographer. Moving to Mashiko in 1978 to train at the Tsukamoto Seito-jo pottery, he would establish his own kiln in 1981 and produce pottery for the rest of his life. He passed away in 2015.

A collection of Ito’s photography, GINZA TOKYO 1964, was published by Morioka Shoten on May 5, 2020.

https://soken.moriokashoten.com/items/2dabee933141

YOSHIYUKI MORIOKA

Bookstore owner

Yoshiyuki Morioka (b. 1974, Yamagata Prefecture) is the owner-director of Morioka Shoten. His publications include Koya no Furuhonya ("The Used Bookstore of the Steppes"; pub. Shobunsha) and BOOKS ON JAPAN 1931–1972 (pub. BNN). He has been involved in exhibitions such as KOGEI to live together (Shiseido Gallery) and Ikei to Kogei ("Reverence and Craftwork"; Yamagata Biennale). In recent years, he has often worked as a producer and promoter of clothing labels. He writes the column "Morioka Shoten Diaries" on the website of Kogei Seika, an art magazine published by Shinchosha.