An Exploration of Modern Ginza

An Exploration of Modern Ginza — IV. A happy coincidence at Kyukyodo

2021.04.20

Photography by Ko Ito

Words & Illustrations by Yoshiyuki Morioka

The Summer/Autumn 2020 issue of Hanatsubaki included an essay by Yoshiyuki Morioka, the owner of Ginza’s Morioka Shoten bookstore, on the relationship between Ginza and Shiseido. In this online column, Morioka ties together the past, present, and future of the district through reference to various books and events.

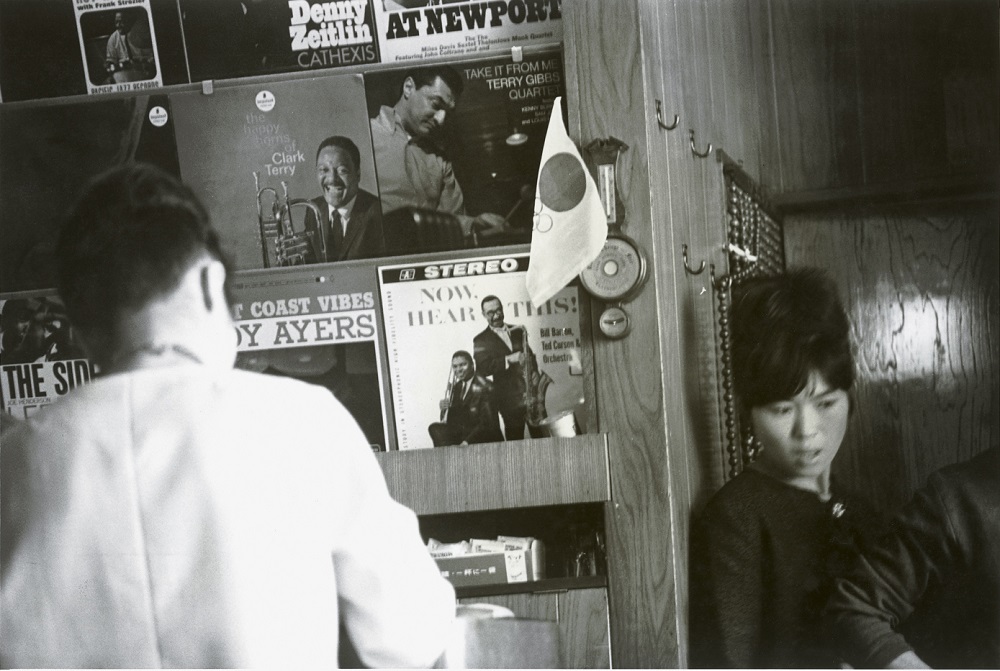

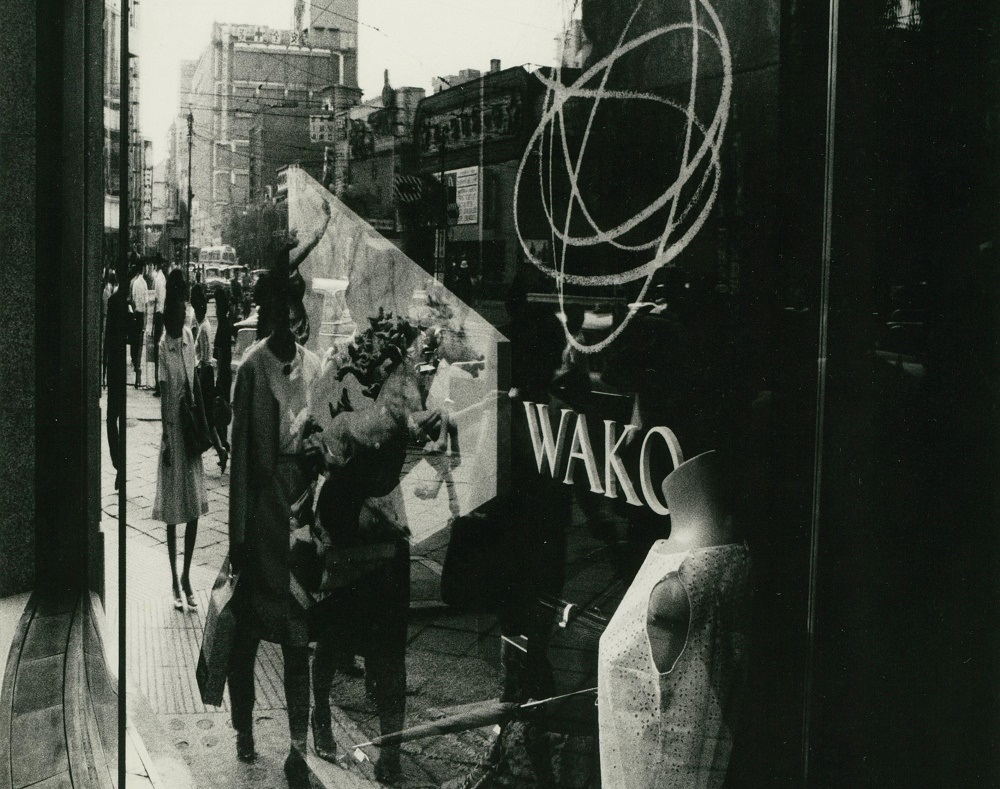

Ginza has always been a stomping ground for iconic figures of the day, and all the excitement and drama that it has seen can be felt in the air even today. So join us on an imaginary walk around Ginza, guided along by the photographs of Ko Ito, a photographer who was taking snapshots of the district around 1964.

IV. A happy coincidence at Kyukyodo

The other day, I received a letter from Germany. Despite the wide variety of digital tools that we have at our disposal today, occasions like this tend to renew my appreciation of the handwritten letter. What letter paper should I use, what envelope? What about the stamp? Letters offer such exciting choices, and they are a joy to receive too. This particular letter had been sent to me by someone who lives in Germany, and both the paper and the envelope were made by Kyukyodo.*1

Well, if I was going to send a reply, I should surely use Kyukyodo stationery too. So, on that day in June, I set out from the Suzuki Building and headed for the store in Ginza 5-chome. As I crossed the Ginza 4-chome intersection, I caught a whiff of incense: it was coming from the entrance of Kyukyodo, where they were doing a sale on incense. It was in 1877 that Prince Sanetomi Sanjo, who was chancellor at the time, conferred on Kyukyodo the secret incense blend formulas that had been in his family for nine centuries; these formulas, which were also favored by the Imperial Household, have been passed down ever since. It is amazing to think that we can still enjoy today an incense blend that has been preserved since the Heian period (794–1185). Even in The Pillow Book (a Heian-period book of essays and musings), we find “lighting fine incense and lying alone” and “washing one’s hair, applying make-up, and putting on a robe suffused with incense” under its list of “Things That Send One’s Heart Aflutter.”

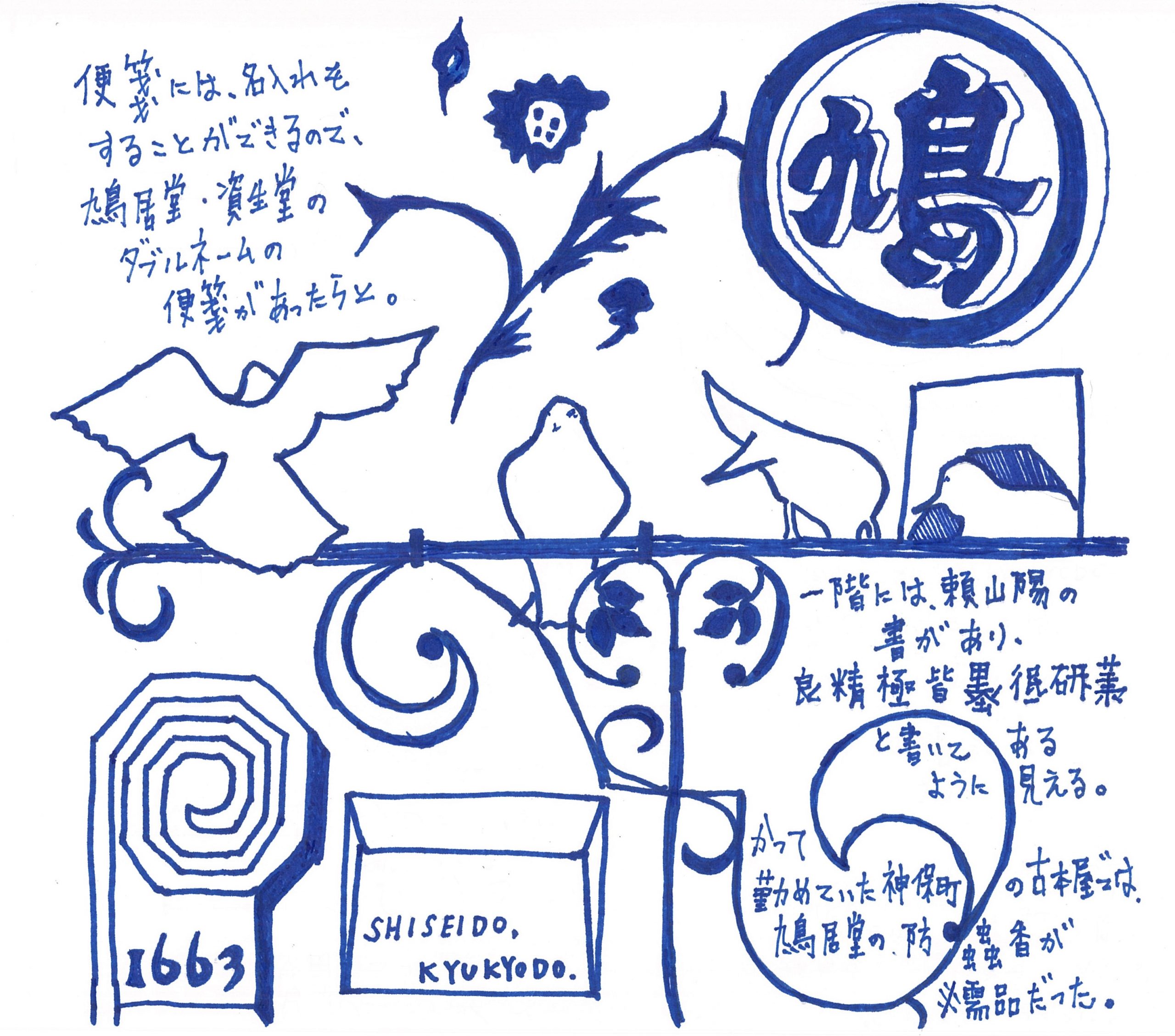

On the left side of the Kyukyodo building’s façade, we find engraved the number 1663: the year when the store was founded in Kyoto. An apothecary shop to begin with, it is said to have started producing incense because of the raw ingredients shared by incense and Chinese herbal medicine. A little research revealed that the potter and painter Ogata Kenzan was born in Kyoto that same year.*2 Kenzan’s pottery work includes some incense burners; perhaps he too shopped at the Kyoto Kyukyodo.

And on the right side of the façade, the number 1880: the year when Kyukyodo opened its first Tokyo branch in Ginza. How did they transport the merchandise from Kyoto to Ginza in those days? The railroad between Kyoto and Kobe had already been completed by then, so perhaps the products were first taken to Kobe by rail, shipped from there to the Port of Yokohama, then finally to Shimbashi by rail again. Though we don’t know the full truth, it’s exciting just to imagine how it might have felt to be at Shimbashi Station on that particular day in 1880, waiting for the steam train to arrive with the goods.

Envelopes and letter paper can be found on a shelf by the counter on the first floor. I chose a paper set called “The Letter,” which had Kyukyodo’s logo—two doves facing each other—on its letterhead. I also found an envelope named “Yushin,” which might be translated as “I Have News” or perhaps “Message Inside”—but I realized that it can also be read as “Arinobu,” as in Arinobu Fukuhara, the founder of Shiseido. So, I bought that too. There were ladies exchanging words about the seasonal letter pads: one was saying, “I’ve used the ‘Hydrangea’ one already, I think I’ll go for ‘Morning Glory’ this time.”

I was intending to post my letter at the Ginza Post Office, which uses a special “scenery postmark” (a decorative postmark that is unique to the post office and the district) depicting the Ginza 4-chome crossing; with that on the stamp, it will be clear as day that the envelope was acquired at Kyukyodo’s Ginza branch.

But what stamp should I use? I collected stamps avidly as a child, and I seemed to recall there being a stamp featuring Ogata Kenzan’s pottery… I looked it up, and it turned out to be the New Year’s gift stamp from 1973. Come to think of it, my addressee is one year my senior, which means… born in 1973! This was a lovely little coincidence, which all happened over a Kyukyodo envelope. It was too good to pass by: I put the Kenzan stamp on the envelope and sent the letter off to Germany, praying for a chance to meet up in Ginza someday.

*2. Ogata Kenzan (1663–1743) was born the third son of Ogata Soken, a wealthy textile merchant based in Kyoto. His elder brother was the painter and lacquerer Ogata Korin. Known as a potter as well as a calligrapher and painter, Kenzan’s work is reputed for its almost literary flair that was free of both vulgarity and ceremony.

Contributors

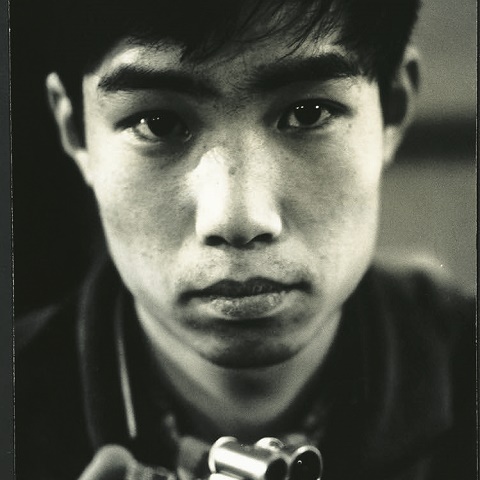

KO ITO

Photographer

Born 1943 in wartime Osaka, Ito was shortly evacuated with his parents to his father’s family home in Wakuya, Miyagi Prefecture. In his sixth year of elementary school, he transferred to a school in Uzumasa, Kyoto, moving there on his own. In 1955 he enrolled at Meiji Gakuin Junior High School in Tokyo, then went on to study at the Tokyo College of Photography from 1961, later joining its teaching department after his graduation in 1963. He held two photography exhibitions during this time. After leaving his post at the school in 1968, he became a freelance photographer. Moving to Mashiko in 1978 to train at the Tsukamoto Seito-jo pottery, he would establish his own kiln in 1981 and produce pottery for the rest of his life. He passed away in 2015.

A collection of Ito’s photography, GINZA TOKYO 1964, was published by Morioka Shoten on May 5, 2020.

https://soken.moriokashoten.com/items/2dabee933141

YOSHIYUKI MORIOKA

Bookstore owner

Yoshiyuki Morioka (b. 1974, Yamagata Prefecture) is the owner-director of Morioka Shoten. His publications include Koya no Furuhonya ("The Used Bookstore of the Steppes"; pub. Shobunsha) and BOOKS ON JAPAN 1931–1972 (pub. BNN). He has been involved in exhibitions such as KOGEI to live together (Shiseido Gallery) and Ikei to Kogei ("Reverence and Craftwork"; Yamagata Biennale). In recent years, he has often worked as a producer and promoter of clothing labels. He writes the column "Morioka Shoten Diaries" on the website of Kogei Seika, an art magazine published by Shinchosha.