90s in Hanatsubaki

#1 Editing for Freedom: Meeting Elein Fleiss, Editor-in-Chief of Purple

2021.06.04

Words by Nakako Hayashi

Photography by Mayumi Hosokura

In the 1990s, there was a magazine that was very influential among those with an interest in fashion, photography, and art. Launched in Paris, Purple could be purchased in far-flung cities at stores that stocked books about art and so on—you could buy it in Tokyo, naturally, but also in, say, Lisbon, Melbourne, or Hong Kong.

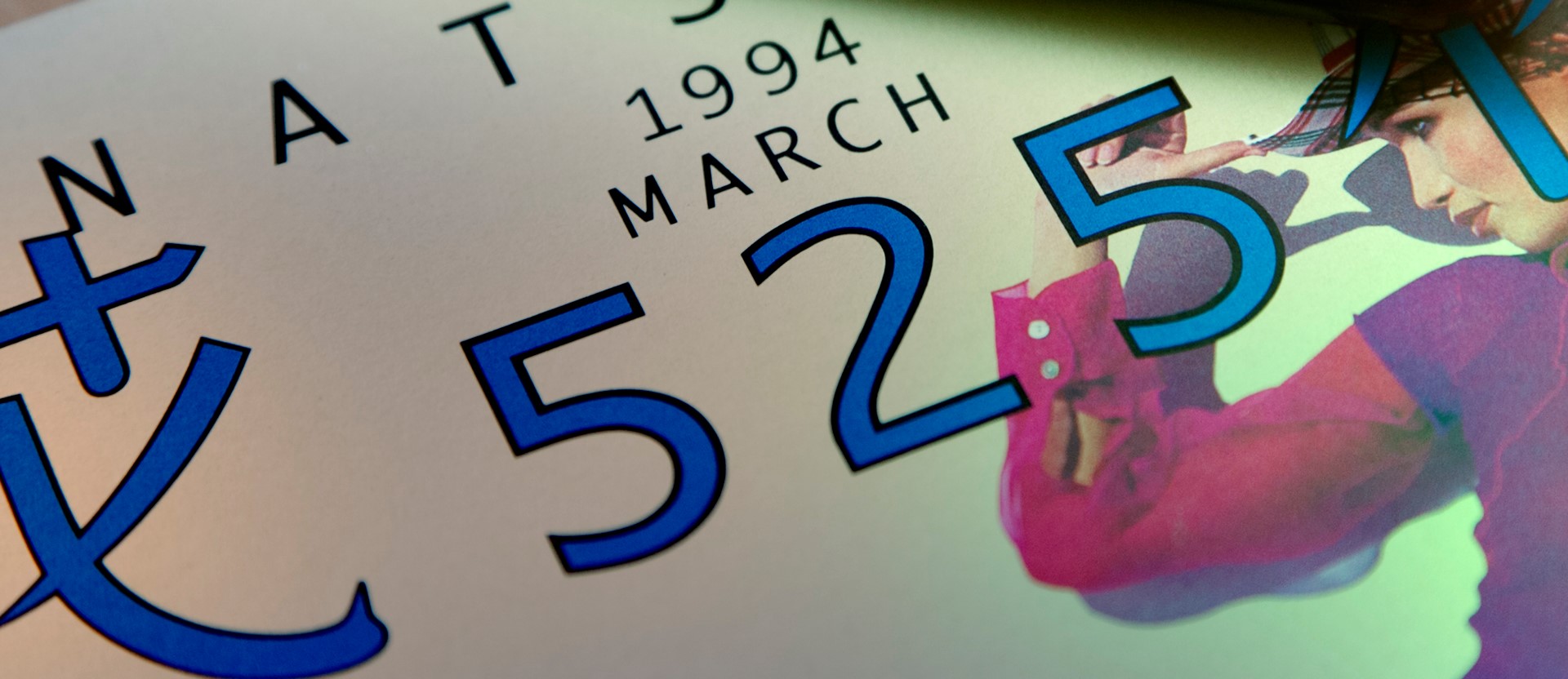

I first went to Paris Fashion Week in 1993. Back then, there weren’t too many invitations to fashion shows going around, so when I wasn’t at a show I visited museums, galleries, bookstores and so on, seeking out information and experiences that might serve as inspiration for Hanatsubaki. It was on one such visit to the Pompidou Center’s bookstore that I came across Purple Prose. The clerk told me it was “a good magazine.” At the time, I was writing a column called “Covers” in which I spotlighted four foreign magazines every month. So I purchased an issue of Purple Prose on the spot, knowing I’d probably find a way to write about it, as there were a number of other art magazines coming out that were exploring new directions.

When I joined the editorial team at Hanatsubaki, the editor-in-chief was Keiko Hirayama. I was completely dazzled by how she constantly traveled abroad for work and socialized with all kinds of artists in Japan and elsewhere, despite being roughly my mother’s age. In the office, there was a shelf with all the magazine’s annual volumes—books that bind together every issue from a given year—dating back to the 1950s. When I checked the volume from 1966, the year of my birth, Hirayama-san’s name was already there in the staff credits. And in the 1965 volume too. It amazed me to think that my boss was someone who had been working here since before I was born. She instilled many things in me, but I think her most important lesson was: “Go meet people.”

I get nervous when I meet someone for the first time; it definitely isn’t my strong suit. Noticing my reservations, Hirayama-san said, “I was like that too, you know.” I couldn’t believe it. But I guess it must have been true. “As editors, we ought to go meet people whenever we can.”

So I went to meet Elein Fleiss too. She was the woman who edited Purple Prose. She was two years younger than me, yet she was the editor-in-chief. Wow. To be precise, I tried to meet her. But as I only had a few days left in the country, we weren’t able to make it work. When it became clear on the phone that our schedules wouldn’t align, she said, “When will you next visit?” I really hadn’t expected her to be thinking about a next time. I wasn’t sure when I’d be able to come again—but the fashion show season rolls around twice a year. Perhaps I could meet her in half a year.

And so I would get in touch with Elein every time I was in Paris for work, and we started meeting up. As we were both editors, there were always things we wanted to show one another. I found it peculiar that Elein, who ran an independent magazine packed with edgy information, took a liking to Hanatsubaki, a culture magazine designed to communicate the values of a company, Shiseido, to women across Japan. Looking back on it now, I think what she liked was our policy of “reporting on things we thought were good”—an editorial line particular to Hanatsubaki, which doesn’t devote any pages to marketing.

In Tokyo at the time, street fashion magazines aimed at young women, such as CUTiE, were very popular. Although disoriented by the differences between the fashion coming out of Paris Fashion Week and the fashion coming out of Tokyo’s streets, I wanted Elein to know about contemporary Tokyo, so I’d sometimes bring her the latest photography collections released by Little More, by artists like Takashi Homma or Yurie Nagashima. I’d show her something or other and she’d immediately react: “Why don’t you and Takashi do a piece for me together?” I was glad for these opportunities that she gave me.

Speaking with Elein, I immediately realized that Purple and Hanatsubaki had entirely different editorial approaches. Hanatsubaki had a long history, and with that history came an established style that has been passed down through successive editors. Purple was set up by a couple who had worked in contemporary art—curator Elein Fleiss and critic Olivier Zahm —and so, even when they covered topics in other fields, they did so in a completely different way from what was considered normal in those fields. Take, for example, the first time they did fashion photography (Purple Fashion vol. 1). They bypassed stylists, hair and make-up, professional models—all the staff that would usually be seen as essential when doing fashion photography—and tried to create images with only designer clothes and the photographer. Those who have been involved with a shoot for a fashion magazine will know well that this isn’t the “usual” way of going about it. Of course, it differed from my own experiences of fashion shoots for Hanatsubaki.

What one saw in their world was freedom. Freedom and equality. Photographers and fashion designers talking on equal terms. One of the photographers who appeared on the scene in those years is Wolfgang Tillmans; I sense something of the same spirit in the experiments he was conducting at the time through the media of fashion photography and clothing. Elein Fleiss was born on April 15, 1968. This was the year the May 1968 revolution erupted in Paris. I’ve known her for a full 25 years now, so I’ve long come to understand that a yearning for freedom, for equality, is her ethos in life, the guiding principle in everything she does—but this was already more than apparent in that magazine Purple, right there at the start of her career.

Translated by Art Translators Collective

Contributors

Nakako Hayashi

編集者

Hayashi spent her time at Shiseido, from 1988 to 2001, on the editorial staff of Hanatsubaki. She learned the essentials of editing from Keiko Hirayama, the renowned editor-in-chief who was in charge when Hayashi joined, and art director Masayoshi Nakajo. Working in Ginza’s unique climate and the liberal atmosphere of Shiseido’s Advertising Department at the time, she forged deep friendships with creators both Japanese and foreign. After going freelance, she founded her own magazine here and there while continuing to write for other publications. She currently writes the column “90s in Hanatsubaki” for Web Hanatsubaki. Hayashi supervised the exhibition Photography and Fashion Since the 1990s, which ran at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum from June 2 until July 19, 2020. She is the author of Kakucho suru fasshon (“Expanding Fashion”), which inspired the exhibition You reach out – right now – for something: Questioning the Concept of Fashion at Art Tower Mito and Marugame Genichiro-Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art; she also edited and co-wrote Kakucho suru fasshon Dokyumento (“Expanding Fashion: Document”) and edited Andrew Durham’s Set Pictures: Behind the Scenes with Sofia Coppola. (Avatar illustration by Erika Kobayashi)

http://nakakobooks.seesaa.net/

https://hereandtheremagazine.com/

Mayumi Hosokura

Photographer

Hosokura’s photography and films deal with youth and sexuality. Her photography collections include KAZAN (pub. artbeat publishers), Transparency is the new mystery (pub. MACK), Crystal Love Starlight (pub. Tycoon Books), and Floaters (pub. Waterfall).

http://hosokuramayumi.com